In this guest blog post, Anne-Lise Harding shares some of the practitioner research she has carried out during her first year working in the House of Commons library with Select Committees, and the specificities of their information literacy needs. Anne-Lise is Senior Liaison Librarian at the House of Commons and the Government Libraries Sector Representative for the Information Literacy Group.

In my first posts for this blog (part 1, part 2, and part 3), I discussed grappling with the information literacy needs of highly-skilled researchers and the specificities involved in working for Select Committees.

At the end of my last blog post, I highlighted the modules to be developed for the Information Scrutiny programme and set out the intention for this post; to talk about co-creation.

Co-creation is a process I found immensely valuable when I worked in Further and Higher Education and I wanted to explore how I could replicate the same process in the workplace, with a completely different audience.

My colleague Phil Abraham (you can find him on Twitter) and I tasked ourselves with developing one module per month. This included writing a lesson plan, researching content, and peer-reviewing each other’s work. This was an ambitious timeframe and most of the time we stuck to it rigorously.

From the start, I had the intention of anchoring the information literacy knowledge from the modules with clear examples of what some issues or solutions looked like in day-to-day work practices.

As Senior Liaison Librarian, I have developed strong links with Select Committee colleagues. This wasn’t easy during the pandemic and I took a more formal than informal approach to liaison but, through delivering training, solving queries, and attending meetings, I had some contacts I knew would be keen to support a peer-review process. I also advertised through one of our regular e-bulletins and soon a team of 10 peer-reviewers had offered to help us (including Diversity champions). All peer-reviewers had a 15-minute meeting with me to discuss what would be involved and their availability. The short meeting time ensured that it wouldn’t impact on their workload significantly, whilst meeting with me ensured buy-in and a more personal approach to the whole task.

We wanted to make the peer-review process as easy and straightforward as possible:

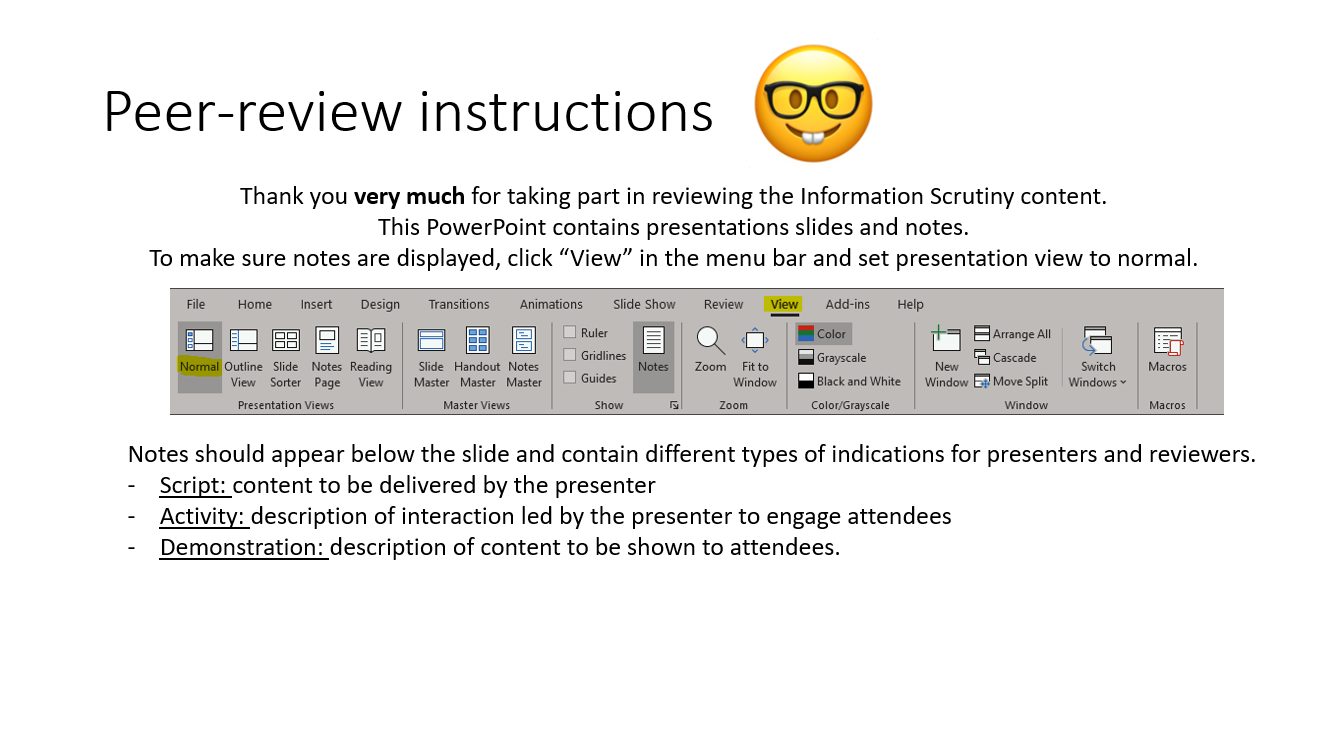

- Peer-reviewers had a month to submit feedback. They would receive a shared link to the PowerPoint with slides, slide notes and instructions by email and then, 3 weeks later, a gentle reminder

- We invited two types of responses about the content

- Firstly, general comments such as answers to “does the knowledge flow well?” or “Is this advice practical for your job role? Why?”. We asked peer-reviewers to send answers to those by email

- Secondly, using the “comment” function in PowerPoint, we left specific comments on slides, usually when we needed specific feedback, or we needed a concrete example of how peer-reviewers had experienced a phenomenon before. We asked the peer-reviewers to answer comments in the PowerPoint

- All instructions for the peer review were included in the PowerPoint. There were 3 slides. The first two showed how to display the comments pane and how to read the slide notes. We made a concerted effort to make the peer-review process easy for all users and this included not taking for granted their level of digital literacy. The last slide contained general questions about the content.

This format was very well-received, with peer-reviewers commenting on how easy the process had been. All stuck to their one-month deadline.

All the received feedback was imported into a shared document and colour-coded by peer-reviewer to analyse the responses. We collated similar comments, highlighted divergences, and ultimately produced a list of changes to be made to the content in response to the feedback.

This approach allowed Philip and I to test our content, ensure its relevancy and its impact. Another unintended consequence of the peer-review process has been the peer-to-peer advertising of the content.

In my next instalment, I will discuss delivering the first module of the Information Scrutiny Programme and early reactions to the content.