Thank you to Dr Julie Greenhough (@EPQGuru), Extended Project Qualification Coordinator at St Benedicts School in London, for this festive-themed post.

I must begin with a confession; I have lied twice to year 7 since the academic year began.

Lie number one I tell every September when we start library lessons in English. I tell the class that our School Librarian, Ms Wallace (@libraryWallace) has read all of the books in our school library. How else can she make recommendations I tell them? This induces a moment of shock and awe, especially when they find out that the library currently holds 16,167 books. Of course, she is a very fast reader, I reply when they ask how she can find time to do this. At some point in later years, one or two may sidle up and murmur that they now know that I was fibbing, but the majority will carry that deception with them.

Dictionaries define a lie as an untruthful assertion intending to cause belief in the truth of a statement that the speaker believes to be false and therefore it involves an intent to mislead, deceive[i]. Clearly, I have deceived year 7 about the School Librarian.

So far, no one has called out my lie unlike what we see happening elsewhere. ‘Well, we’re currently interrupting this because what the President of the United States is saying, in large part, is absolutely untrue’, commented the CNBC anchor on the baseless post-election claims against illegal voting in America. Facebook and Twitter now put warnings on some of the tweets issued by POTUS where lies and falsehoods are proven. All well and good. Or is it?

As Kuper (2020)[ii] in an article in ‘The Financial Times Magazine’ writes, ‘Post-lie fact-checking rarely has the impact of the initial lie’. Year 7 could check with the School Librarian as regards the veracity of my claim, only to be met with her support of it and spreading the deception yet further. The impact of the initial lie will be greater than the unveiling of it. Often, pupils do not know how to spot a lie let alone how to go about proving the falsehood. I deceive them because I am their teacher, there are power dynamics at play and they are default set to believe I am telling them the truth. Just like when their parent/guardian tells them that they must go to sleep on Christmas Eve or else Father Christmas will not come.

Which brings me to lie number two. Mid lesson and Aniela exclaims, ‘But Miss, there’s no such thing as Father Christmas!’. A hush descends on the room. I cast rapid glances to all the pupils to check for the tell-tale face wobble that will indicate that there are still some pupils who are holding onto that belief as a childhood truth, to see whose world view has shifted, whose mind-set needs adjusting. Tell the truth we are exhorted; do not lie. How far do I take this now Father Christmas has joined the dilemma? I opt for the utilitarian view of J.S. Mill (1861)[iii] that we should do whatever produces the happiest outcome and do not make any comment in response to Aniela’s statement. This is an occasion where happiness born of a deceit is a happiness I deem worth them having. After all, how do we know that Father Christmas does not exist? We may know there is no Father Christmas but how do we know that this is so? We end up in a situation of not knowing how we know.

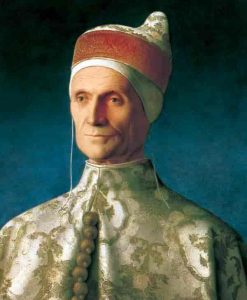

A Google search on Aniela’s statement ‘is Father Christmas real?’ yields me 570,000,000 results in 0.62. Which may impress year 7 but we know that googling to look something up is not actually the same as researching something. Teaching the Extended and Higher Project Qualifications (EPQ/HPQ) has shown me that the majority of pupils seem to think that a database is a source and lack the understanding of how a database works. To be frank, this also applies to rather a lot of adults. A simple example is to ask them to find an image of Doge [iv]. Without fail, they google and find image A as opposed to image B. Some even find image C. Funny? Momentarily, maybe. But what this false knowledge assumption may lead pupils to is no laughing matter, is it? In the current Covid context is it could be literally life-threatening.

Pupils need to know and to be taught how to recognise that some of the internet is wrong. This requires as large a mind shift as does finding out your English teacher has lied to you and that Father Christmas is not real. The pupils are not the ‘savvy, reflective, critical, consumers of information’ (Asher, 2011)[v] that we would want them to be or that they need to be in the current challenging context. Pre pandemic, only 2% of young people in the UK had the critical literacy skills needed to tell if a story was real or fake (NLT, 2018) [vi]. The same report highlighted that 45.9% of secondary school pupils found out about the news via Snapchat. My own experience of teaching GCSE English Language supports this. The pupils are required in the exam to write a letter to someone, usually a local MP or newspaper despite never having written nor received a letter in the post. They could also be asked to write a broadsheet style editorial or an article for a print based newspaper or magazine. None of the pupils in my key stage 4 classes in recent years have ever looked at a broadsheet print paper; they may occasionally look at local free print papers. This one example is so indicative of part of the problem namely the time lag between the need for action and the action taken in education via the National Curriculum, which is invariably behind the curve of digital literacy change. I wonder now what the influence of TikTok (available worldwide from August 2018) that styles itself as ‘Real People. Real Videos’ may be on pupils news and factual consumption?

What to do? Direct them to fact-checking sites such as FullFact. Teach them to think like SHEEP using the infographic from First Draft [vii] Encourage them to adopt a sceptical mind-set, even with what their teachers may tell them. To think before they share online material so they do not add to the fire of falsehood by giving oxygen to its flames.

Yet now, even by adopting such a mind-set it is becoming harder to challenge lies and establish truth. The credible seeming headline making the claim that a US government agency has declared Covid-19 did not exist had even the fact-checkers struggling to check its veracity, so credible was its image that it was able to bypass online fact checkers [viii]. Transpires it was from ‘The Light’, a self-published print newspaper that claims to be a ‘truthpaper’, another lexis to add to the growing pandemic lexicon.[ix] ‘We can have all the checks, balances, tools, lists, websites and advice in the world but it is the right mind-set which is crucial to not get tricked’ (FirstDraft 2019).

We are all, the pupils included, free to choose our own truth but unless we close the time lag between need and action with regard to critical digital literacy skills, unless we change the educational mind-set then lies, even my own, will proliferate and become ‘truth’. We are still a long way off ensuring the right of every one ‘to be able to acquire the critical literacy skills they need to navigate potential pitfalls’ online (NLT, 2018, pg 28). Steps are being taken, as the work by Professor of Media and Education Julian McDougall and that of the action group on Information Literacy from CILIP demonstrate. But more is needed, and fast. Oh, and just in case I am wrong about Father Christmas and need to reset my own mind-set from adult to child-like, then I will be sure to be fast asleep come Christmas Eve!

[i] The Collins English Dictionary

[ii] S. Kuper ( November 19th 2020) ‘Have journalists finally learnt how to challenge political lies?’ Financial Times Magazine Life & Arts.

[iii] J.S. Mill (1861) ‘Utilitarianism’

[iv] With thanks to my colleague Martin Swan for this example.

[v] Asher ( August 28th 2011) cited in ‘US study shows Google has changed the way students research – and not for the better’ in ‘The Conversation’.

[vi] National Literacy Trust (2018) ‘Fake news and critical literacy’.

[vii] First Draft (December 9th 2019) ‘Think SHEEP’ before you share to avoid getting tricked by online misinformation.

[viii] ‘The Guardian’ (November 27th 2020) J. Waterson ‘How an anti-lockdown ‘truthpaper’ bypasses online factcheckers’.

[ix] See Dr Thorne’s blog on the language of the pandemic ‘Coronaspeak: the language of Covid-19 goes viral’ April and November 2020 @tonythorne007