Darryl Toerien is Head of Library at Oakham School in Rutland. He serves on the National Committee of CILIP’s School Libraries Group (SLG) and the Board of the School Library Association (SLA), and has recently also been elected to the Section Standing Committee for School Libraries of IFLA. He was shortlisted for the Information Literacy Award in 2019 and was part of the Information Literacy Group (ILG) TeenTech Working Group that was shortlisted for the Digital Award for Information Literacy in 2016. Darryl also runs the TeenTech Awards at Oakham School and has been shortlisted for the Teacher of the Year Award in 2016, 2017 and 2018.

The world belongs to me because I understand it,” declared Balzac (Bloom, 1987).

Taken positively, this means that the world and the fullness of its possibilities is open to me. Taken negatively, this means that the world and the fullness of its possibilities is closed to me. Further, that I am vulnerable to those who would take advantage of me, and if I am lucky, this will only cost me money.

For our children, the odds of learning to understand the world are stacked against them, at least in school. Firstly, knowledge, as represented by the taught curriculum, is more or less fragmented into subjects and more or less incoherent across subjects. Secondly, this situation is exacerbated by an educational system that is geared towards exam-focussed, content-driven instruction, and in which there is no time for anything else. Thirdly, the skills and disposition that are necessary for constructing understanding from knowledge from information – which include what may be termed information literacy, and is traditionally the domain of the librarian – are not integral to this system. It could be argued, then, that not only is school not making things better, but that it is actually making things worse. And it is not just our children who pay a steep price – the cost to university and society of students leaving school ill-equipped for life beyond school is steeper still, and this completes a vicious circle.

It does not need to be this way.

As Marshal McLuhan observed, “as we begin, so shall we go” (2008), and so we must begin properly, with who and what education is for. Now if education in school is for enabling children to make sense of their world, then the relationship between the library and the classroom comes into proper view, which is that the classroom leads, or should lead, inevitably and essentially to the library (Beswick, 1967). This does not mean that the library is more important than the classroom, but that acquiring the skills and disposition necessary to make sense of the world requires deliberate and complex collaboration between the classroom and the library, or the teacher and the librarian.

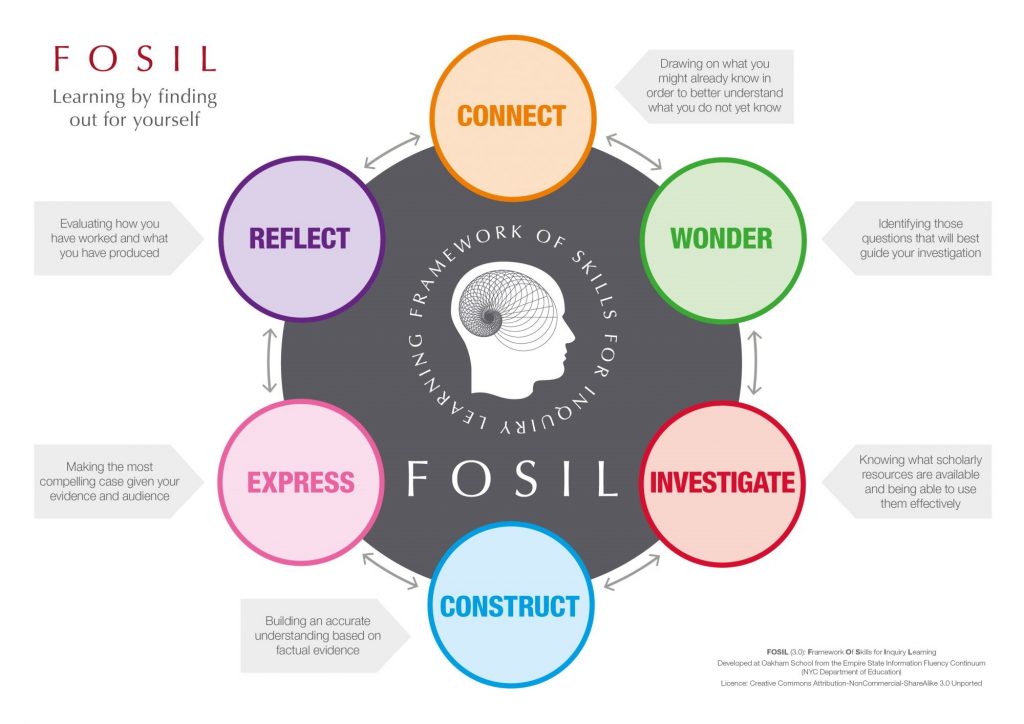

FOSIL is a means to this end, and the FOSIL Group emerged to enable it.

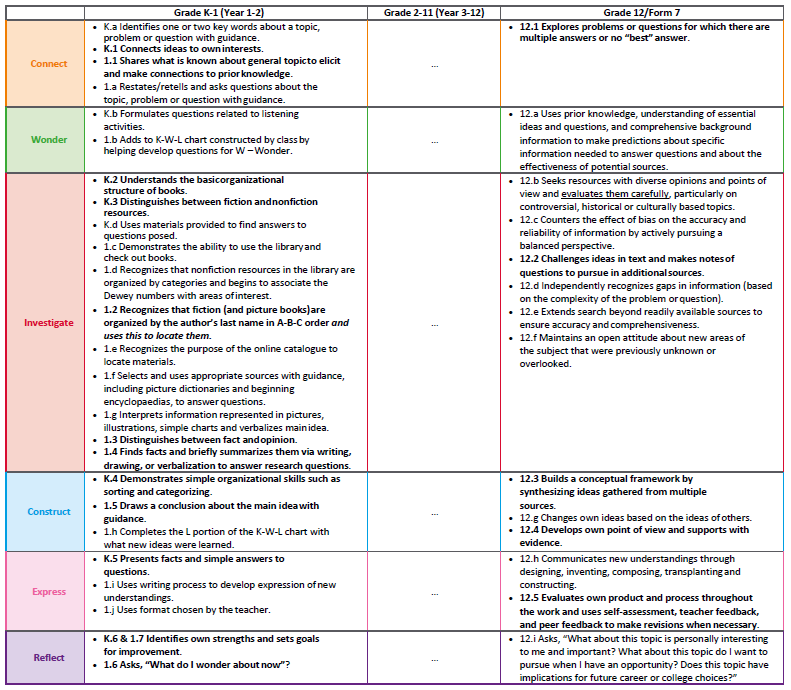

FOSIL stands for Framework Of Skills for Inquiry Learning, which is a model of the inquiry process (see also below) and an underlying framework of inquiry skills, fundamental to which is information literacy. FOSIL is based on the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum, which was developed by the New York City School Library System (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) while under the direction of Barbara Stripling. The New York City school district is the largest in the United States, with more than 1.1 million students in over 1,800 schools.

While this particular model and framework is the focus of the FOSIL Group, we are not limited to it, because all of us are at different points on this journey and some are working with different tools, and this enriches the community.

The development of FOSIL (see E&L Memo 0 | Developing inquiring minds: a journey from information through knowledge to understanding for a more detailed treatment) and the emergence of the FOSIL Group formed the basis of our submission for this year’s Information Literacy Award, for which I was shortlisted and placed third. This also formed the basis of my presentation at LILAC – Information literacy: Necessary but not sufficient for 21st century learning – which may be downloaded from here.

What became alarmingly clear to me in preparing for my presentation at LILAC, and what I would like to focus on here, is the enormity of the task and the gravity of the situation confronting us.

Shortly before LILAC I came across the following infographic on the ENSIL website (European Network for School Libraries and Information Literacy), here.

Problems with the source notwithstanding*, it would seem that a university is inconceivable without a library, and yet the number of schools effectively without a school library is probably growing. I asked the delegates attending my presentation who were from universities (approximately three quarters) whether it would make any difference to them if every single school library disappeared, and their honest answer was, unsurprisingly, no. This is entirely understandable, under the circumstances, but is hardly a stable foundation to build on, whether at university or in the workplace.

Furthermore, it guarantees that students will arrive from school unprepared for learning at university regardless of how effective university interventions are into Year 13, or how effective induction at university is, because by the time students reach this point of transition it is too late to address the problem remedially.

Consider that the framework of inquiry skills underlying the FOSIL Cycle stretches from Year 1 (Kindergarten) to Year 13 (Grade 12).

This represents a foundation of inquiry skills, fundamental to which is information literacy – accompanied by a mindset, approach and attitude to learning – that should be systematically and progressively established over the course of 13 years if the student goes on to university, and up to whatever point s/he exits formal education if not.

Viewed positively, if this were actually the foundation that school established, imagine what learning at university would be like, and lifelong learning more generally. Viewed negatively, can we afford not to lay this foundation?

And here’s the rub – as the engineering adage has it, our system is perfectly designed to achieve the results we are getting. So, to achieve different results, dare we say better results, for our children and those who must follow in our footsteps, if there are any footsteps left to follow in, we will need to change the system, and this will cost us. It will cost us because we will need to find a way to replace an impoverished educational system with a more vital one, one in which being educated means being able to use a library, in its fullest and richest sense, purposefully and effectively. Then we will need to equip every school with a library that is appropriately resourced and staffed, with library staff who have been prepared for the kind of school librarianship that this kind of education will require, which, in turn, will require library schools that are able to do so, as well as schools that prepare teachers. Then, working with our colleagues in university libraries, who will need to be working with their colleagues outside of the library, we will need to raise the bar to take account of the fact that students leaving school might actually be thoroughly prepared for learning at university. And who’s got the time and energy and money and vision for all this?

The FOSIL Group is an attempt to model a different educational reality, one in which teachers and librarians collaborate to enable students to learn by finding out for themselves in increasingly sophisticated and effective ways. Everything on the site to encourage and support this is open and free, because the better we get at getting better, the faster we will get better (Doug Engelbart), and the hour is already late. The 55 members who have joined since the launch of the FOSIL Group during my presentation at LILAC represent 36 very different schools (secondary and primary, with 3 overseas), a university, and a growing number of members working alongside formal education. We have begun as we mean to go – if this strikes a chord, please consider joining us.

*The ENSIL site is © 2019, but the only date that is indirectly related to the infographic is 2010. It also lacks a geographical context, although the page states that the ALIES campaign is initiated by ENSIL, and endorsed by IASL (International Association of School Librarianship) and IFLA | SLRC (International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions | School Libraries and Resource Centers Section, now School Libraries Section). This at least gives me confidence that the infographic bears semblance to a reality (probably global) at some point in time (probably around 2010) – I have reached out to ENSIL for further details, but I have not yet had a reply.

Bibliography

Beswick, N. W. (1967). The ‘Library-College’ – the ‘True University’? The Library Association Record, 198-202.

Bloom, A. (1987). The closing of the American mind. New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks.

Illich, I. (2000). Deschooling Society. London: Marion Boyars Publishers Ltd.

McLuhan, M., Fiore, Q., & Agel, J. (2008). The medium is the massage. London: Penguin Books.

The world belongs to me because I understand it,” declared Balzac (Bloom, 1987).