Adam Edwards and Vanessa Hill of the Sheppard Library, Middlesex University, have kindly provided us with a guest post on the development of their teaching practice and the innovative approaches and resources they use when supporting the development of their students’ information literacy skills.

Game On: Enhancing engagement, interaction and reflection in library workshops – Adam Edwards and Vanessa Hill (The Sheppard Library, Middlesex University)

As librarians who have worked in higher education for more years than we care to remember, we have witnessed many changes to our information and professional landscape, not least widening participation and the advent of the Internet. As a result of these changes there has been a gradual shift in the role of academic librarians away from being the guardians of information who manage and enable access to resources. Increasingly we operate outside the confines of the physical library, guiding students through the proliferation of information and developing their information literacy skills through library workshops. Consequently there is a much greater emphasis on our role as ‘teachers’, a role for which most of us have never been trained.

Here at Middlesex University, a post-1992 institution located in north London, our team of librarians are increasingly innovating in the way library and information skills are taught, as outlined by Edwards (2016). The majority of the team now have teaching qualifications, something actively encouraged to ensure that we are fit for our changing role. In this article we, the authors, describe how our pedagogical practice has evolved over a number of years, paving the way for wider changes in the way our librarians develop information literacy.

What we have done is to introduce the idea of using ‘games’ in our workshops. When we talk about the use of ‘games’, we are not talking about Monopoly or Scrabble, but rather using the language of games, e.g. decision making, interaction, teamwork, competition and problem solving, etc. This is commonly referred to as ‘gamification’, which is defined by Sailer as using the “motivational power of games for other purposes not solely related to entertaining purposes of the game itself” (2013, p.28).

Back in 2008, following a restructure of our service, Vanessa found herself supporting computing and product design engineering students after many years as an art and design librarian. Joined by Adam as her line manager in 2011, it became obvious that change to our pedagogy was necessary for a number of reasons. Vanessa’s lack of subject knowledge for the programmes that she was now supporting, especially computing, meant that preparing traditional, didactic, ‘teacher’ led workshops was no longer feasible. Adam, after many years working as a library manager, was armed only with the ‘teaching’ skills developed early on his career. These skills were clearly insufficient to meet the demands of a changed information landscape where students have easy access to information 24/7.

Inspiration initially came from a workshop that Vanessa attended at CILIP, run by Sharon Markless, on teaching information literacy in higher education (Hill and King, 2010). Vanessa came away from this workshop with five learning principles that underpin how we now teach and are always at the back of our mind when designing library workshops. These are:

- Don’t try and cover too much: We teach three to five times more than students will take in, so concentrate on what will make the biggest difference. Everything else can be consigned to the online learning environment.

- Don’t try and clone your own expertise: It’s not possible to distil your own expertise into a one-off workshop. Students are unlikely to approach information retrieval in the way that librarians do.

- Discussion is powerful: We can learn a lot about students’ understanding from the questions they ask and the feedback they give. What we hear, what they say, what they don’t say can help guide the content of a workshop. In essence, we should begin from where our learners are, i.e. establish prior knowledge, expectations, needs, etc.

- Learning by doing is empowering: Let students discover for themselves. Encourage active participation through a variety of activities, trying things out for themselves, reflecting on their mistakes and finding solutions when things don’t work. After all, un-involved students are less likely to learn.

- Students should be learners, not the taught, working together to learn: Our role is to support and facilitate, not to dictate.

With these principles in mind, we considered what we really needed to teach students in library workshops. We came up with four key areas that now form the basis of the workshops that we offer at every level, from foundation through to postgraduate programmes. These are:

- Thinking about the value of different sources of information, especially in the context of academic writing.

- Constructing usable keywords and search terms to find what is needed and how to refine search results effectively.

- Hands-on self-exploration of relevant resources with no pre-prepared demonstrations.

- Evaluating information found for relevance and quality.

What was then needed was a ‘vehicle’ to enable learning to happen. Inspiration for this came from a workshop attended by Adam at LILAC 2011 (Boyle 2011) on a games and activities based approach to teaching information literacy.

Having established workshop content, we therefore developed games and activities for each key area based on Boyle’s recommended principles, namely that games should be:

- Fun and enjoyable: After all the Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines games as an “activity engaged in for diversion and amusement” (2015).

- Quick: No more than about ten minutes long.

- Simple: Easy and cheap to prepare.

- Easy to grasp and play: No complicated rules.

- Meet a specific learning need or objective: e.g. not playing games for the sake of it.

In addition, Burgun (2013) believes that games should also include an element of competition and decision-making and Zagal, Rick and His (2006) consider that collaboration is a significant factor

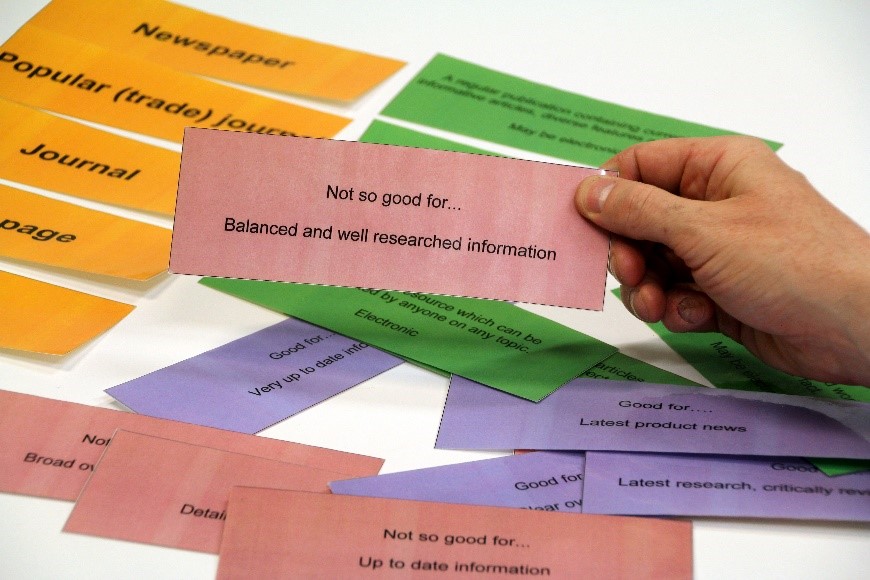

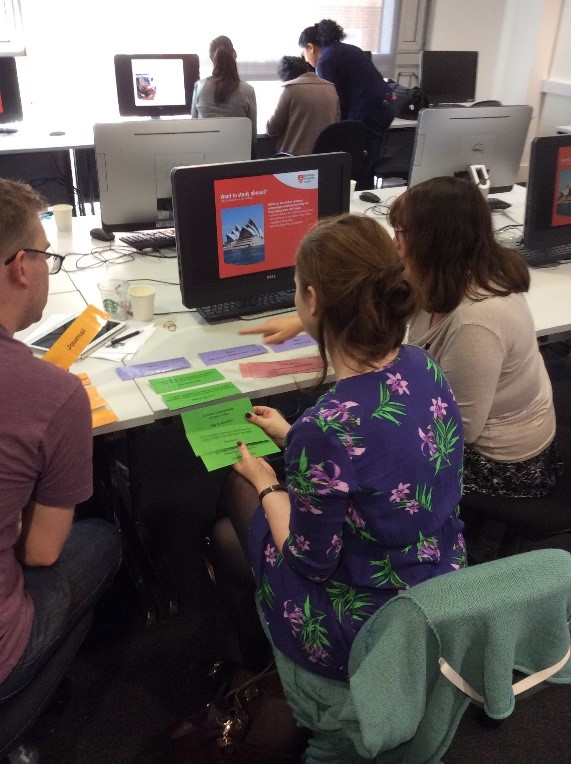

Initially we developed games and activities for 1st year computing workshops, but we have since designed different games and activities for each key area at all levels. As an example, the first game we developed, “Thinking about Resources”, is a simple card sorting game to encourage 1st year students to think about the range and value of different sources of information. Download a template for the cards.

Students work in small groups and are given a set of cards that comprises of five resource cards (Book, Journal, Newspaper, Website, Popular Journal/Magazine), which need to be matched with a definition card, plus a ‘good for’ and ‘not so good for’ card.

As the students undertake the group activity, we can establish their level of understanding from the discussions that we over hear, as well as identifying misconceptions and misunderstanding that can be addressed in feedback following the activity. There are no right or wrong answers as far as the ‘good for’ and ‘not so good for’ aspects are concerned, and students have the opportunity to explain how they have matched the cards. Consider how this approach compares with a more tradition ‘lecture’ approach where the librarian ‘lectures’ concepts to the class. In using this activity, discussion naturally occurs around a number of issues, such as peer review, access and currency,

It is worth stressing that our games and activities do not sit alone. They are used in the context of group discussion and feedback, and encourage collaboration, peer learning, and reflection. We know that our games and activities achieve this. As students take part they are engaged and there is increased interest and motivation. After all, playing games can be a social and communal activity. There is lots of discussion, collective and peer learning. What we hear the students discuss is indicative of what they know and what they don’t know. Students appear to be learning and developing their understanding. Burgun also believes that games teach us how to learn, activating prior knowledge and building on existing skills (2013). This is the constructivist approach to learning, which is the foundation of our changed pedagogical practice. Students seem willing to ask questions and voice opinions. Games indeed can alleviate some of the fear that students experience when using a library – what Walsh (2014) describes as ‘library anxiety’ – as students are able to experiment in a safe environment. We can respond as necessary, challenging misconceptions and filling gaps in their knowledge. Crucially for us, teaching is much more fun, with no one workshop being the same. Thus the use of games in our workshops empowers students to make decisions based on prior knowledge, plan a course of action, consider the outcomes, solve problems, absorb and consolidate new information, and learn from that.

We make no claim that our approach is any more valid than other ways of teaching, but students do appear to be more engaged and feedback is positive. The resources we have developed are publicly available for anyone to use and adapt and we welcome feedback from other librarians who use them.

We would also welcome comments from librarians who use games and activities in their workshops or have experimented with less traditional ways of teaching. In particular, feedback on whether such innovations have changed your practice for the better and what (if any) concerns, problems, and resistance you have encountered from students, academic staff or library colleagues?

Our changed pedagogical practice led us to undertake a joint Doctorate in Professional Studies (DProf) by Public Work on the topic “Demythologising librarianship: future librarians in a changing literacy landscape”. Amongst other things, the thesis explores our professional journey; the potential role of librarians in the development of information literacy; information literacy concepts and models; obstacles to the wider adoption of information literacy in higher education; and the skills and attributes required by the librarian of the future.

References

Boyle, S. (2011) Using games to enhance information literacy sessions. . 18-20 April 2011. London School of Economics: LILAC.

Burgun, K. (2013) Game design theory : a new philosophy for understanding games. Boca Raton: CRC.

Edwards, J.A. (2016) ‘Evolving pedagogical practice at Middlesex University: the state of our art’, SCONUL Focus, (68), pp. 47-57.

Hill, V. and King, S. (2010) Notes from Teaching information literacy in HE: What? Where? How? 9 December 2010. Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals, London, UK.

Merriam-Webster Dictionary (2015) Definition of game. Available at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/game (Accessed: Aug 10, 2018).

Sailer, M., Hense, J., Mandl, H. and Klevers, M. (2013). Psychological perspectives on motivation through gamification. Interaction Design and Architecture(s) Journal, 19, pp.28-37.

Walsh, A. (2014) ‘The potential for using gamification in academic libraries in order to increase student engagement and achievement’, Nordic Journal of Information Literacy in Higher Education, 6(1), pp. 39-51.

Zagal, J,, Rick, J. and His, I. (2006) ‘Collaborative games: Lessons learned from board games. Simulation and Gaming, 37(1), pp.24-40.

An overview of Open Educational Resources (OERs) for information literacy teaching